Introduction

By Marybel Menzies

Jonathan Haidt's thesis in moral psychology posits that our ethical decision-making is primarily guided by intuition, with rationalization following as a secondary process. This perspective suggests that when faced with moral dilemmas, we first experience an immediate response and then seek logical justifications for our intuitive judgments. In our quest to validate these moral stances, we often use convoluted reasoning, attempting to support judgments that may lack a solid logical foundation. This results in a cognitive dissonance between our intuitive moral compass and our desire for rational justification.

Haidt's theory resonates with a philosopher named in the last newsletter—David Hume—and his philosophical assertion that reason is subservient to “passion” (feeling) in matters of moral judgment. This striking parallel between contemporary research and centuries-old philosophy raises an intriguing question: Was Hume correct all along in his understanding of the human psyche? The convergence of these ideas across time and disciplines suggests that our moral judgments may indeed be more intuitive than we care to admit—with reason often playing a supporting role. This perspective challenges us to reconsider the foundations of our moral beliefs and invites us to explore the delicate interplay between intuition and reason in shaping our ethical landscape.

At our latest Curiosity Café, moderated by Professor Yoel Inbar and our own Zachary Grey, we explored the nature of our moral intuitions and whether they really ought to be seated center-stage in our moral reasoning.

Featured Content:

Curiosity Café Recap: Moral Intuitions

Community Survey

Upcoming Events

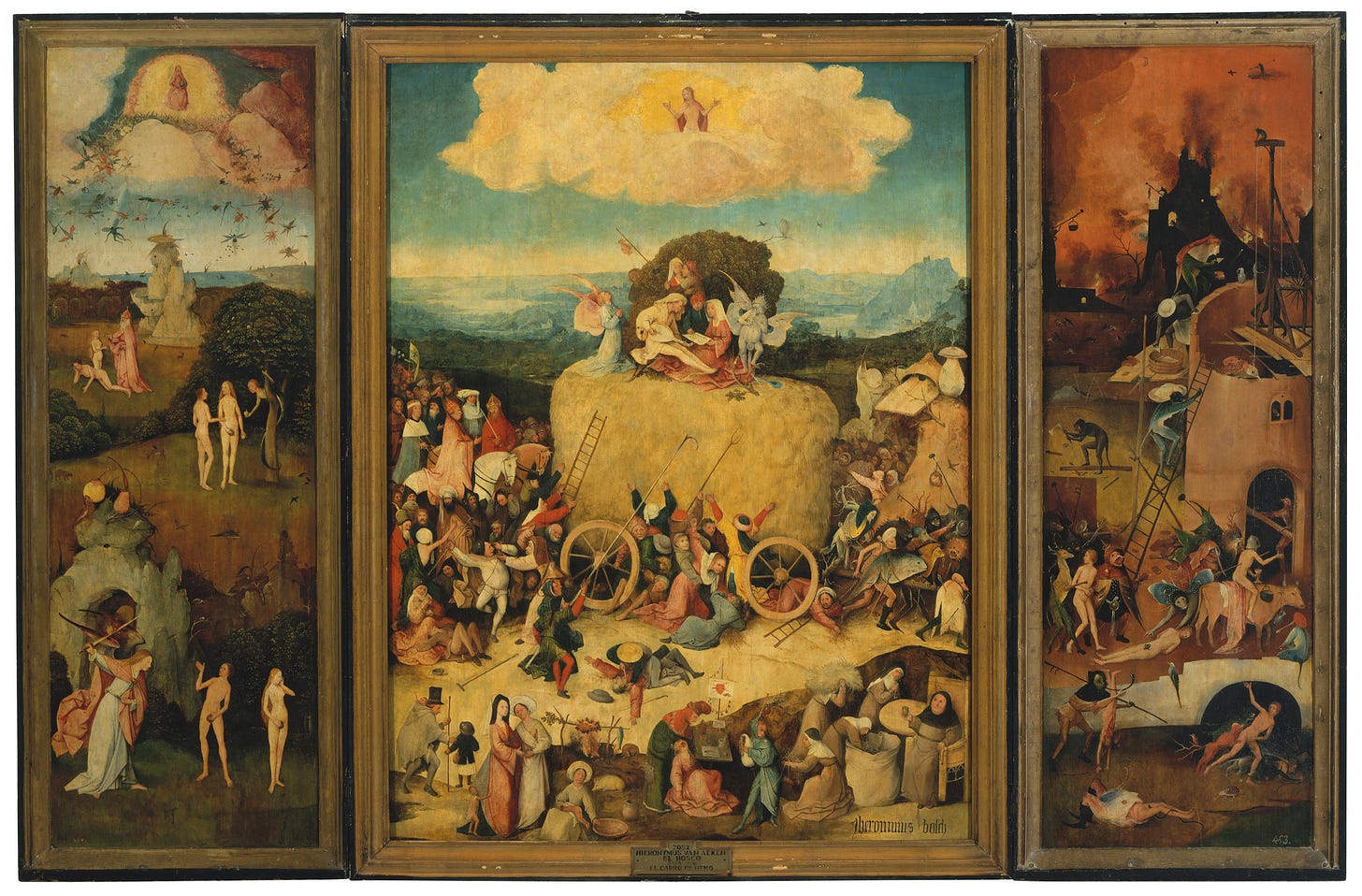

Arts & Culture: The Haywain Triptych by Hieronymous Bosch c. 1490-95 Museo del Prado

Toronto Events

Readings & Resources

Curiosity Café Recap: Moral Intuitions

By Marybel Menzies

We began the first half of the discussion by reflecting on a case study used by psychologist Jonathan Haidt to examine the power of our moral intuitions. The case runs as follows:

Mark and Julie are brother and sister. They’re travelling through France together. On their trip, they spend the night in a house on the beach. They decide it would be interesting to have sex with each other once. It would, at the very least, be a new experience for both of them. Julie is taking the pill already, but to be sure, they also use a condom. They enjoy the experience but decide not to do it anymore. They’ll keep it a secret – an experience that brings them closer together.

The purpose of the example: to demonstrate the "stickiness" of intuitions, to (descriptively) account for why / how they arise, and to understand the limitations in their accuracy (measured by the discrepancy between the objective features and the subjective perception or beliefs about said features). We then asked,

What is your answer to the Mark and Julie question? Does your considered (“deliberative”) answer differ from your initial (“intuitive”) answer?

If you answered “morally wrong,” why do you think that? Is there anything that could change your mind (i.e. anything about the case that you could change to make you think it’s morally acceptable for Mark and Julie to have sex)?

What moral intuitions do you think are pushing you towards one answer or another?

What kinds of other moral questions or situations do you think evoke strong moral intuitions (feel free to draw on life experiences here)? Can you come up with a taxonomy of moral intuitions (i.e., what type of considerations or values tend to be morally salient?) based on these other cases?

After our small group discussions, a survey was posed to the larger group. That is, our moderator asked, by show of hands, how many of us think what Mark and Julie did was morally wrong? Surprisingly, it was nearly a 50/50 split. Why was this result surprising? The data collected by Haidt and team showed that on the first pass reading, roughly 80% of people believed that what they did was morally wrong, whereas even upon further examination, 68% of people still thought it was wrong.

Many participants noted a discrepancy between their gut reactions and their considered opinions. This divergence showed the influence of societal and cultural norms on our initial moral intuitions—prompting a cautionary approach to relying solely on these immediate responses.

Participants then emphasized the role of maintaining curiosity and open-mindedness in reading the prompt. This enabled them to engage with it in a way that was critical and less susceptible to emotional reactions. To consider an analogy, imagine answering the following conditional: if 1 + 1 = 4, then will 1 + 1 + 1 = 6? Well, if you endorse the antecedent, then you must endorse the consequent. Nevertheless, it illustrates how challenging it can be to suspend disbelief even if a judgment would conflict with previously held beliefs.

From there, we explored the moral concerns surrounding the scenario. For example, this type of behaviour typically has adverse consequences, such as birth defects, social ramifications, normalization of generally impermissible behaviour, and a negative alteration of family dynamics.

However, if we examine the case from a nuanced perspective, we can see that these considerations have been accounted for. This led some participants to suggest that morality should not be based on universal moral prescriptions but rather on a case-by-case assessment.

Some participants identified their moral discomfort as rooted in historical and evolutionary concerns about the potential consequences of normalizing such behaviour. Even within the bounds of the thought experiment, the implications for generalizability and universalization remained troubling. Others found themselves drawn to broader frameworks of morality, such as virtue ethics, which focuses on qualities like courage or restraint, or teleological reasoning, which considers how actions align with human flourishing and the “proper ends” of relationships. Within these frameworks, Mark and Julie’s actions were seen as potentially undermining virtues or violating the intrinsic purposes of familial bonds.

However, caution was urged against relying uncritically on moral intuitions shaped by cultural biases. History is replete with examples of entrenched, unexamined moral beliefs—such as the stigmatization of homosexuality—that have perpetuated harm. Yet, moral intuitions, imperfect as they are, can also act as valuable checks against the excesses of abstract moral reasoning, inviting us to reassess principles that might lead to counterintuitive or troubling conclusions.

Ultimately, the discussion underscored the complexity of moral reasoning and the interplay between intuitive, deliberative, and cultural influences. It highlighted the importance of examining moral principles with both openness and skepticism, striving to balance respecting long-standing values and critically interrogating their origins and implications.

The second half began by looking more closely at whether moral intuitions serve as good justifications for moral reasoning. The focus was on building on the limitations of intuition by incorporating aspects of the limitations of reasoning as well (hence the discussion on how / why intuitions might be appropriate in some cases). Then, we move towards determining when intuitions are appropriate for affecting our judgments/decisions and when they are not, normatively speaking. Finally, we try to reconcile the fact that intuitions can be the cause of many disagreements and investigate what that means for how disagreements unfold.

The discussion revolved around the interplay between moral intuitions, reasoning, and the frameworks we use to assess right and wrong. Moral intuitions, it was noted, do not arise in a vacuum. They are shaped by biological, cultural, and experiential factors, such as the evolutionary instinct to avoid inbreeding due to the risk of defective offspring or the internalization of cultural norms that may vary widely between societies.

For instance, while incest is widely taboo in many cultures, in others, cousin marriage is accepted and even encouraged. This cultural variability suggests that our intuitions should not always be taken as natural or self-evident truths.

Some suggested that despite their variability, intuitions can sometimes serve as valuable guides, particularly in time-sensitive situations. Just as fear can prompt us to flee from danger without deliberation, moral intuitions can provide quick, actionable judgments when there is no time for extended reasoning. However, the appropriateness of relying on intuitions depends on the scale and stakes of the decision. For personal, low-stakes matters, intuitions may suffice, but when making decisions with far-reaching consequences—such as legislating policies—extensive moral reasoning becomes indispensable.

We also explored the potential rational basis of intuitions. Some participants likened intuitive moral judgments to the instincts of a chess grandmaster, honed through extensive experience and capable of outperforming a novice's deliberate reasoning. However, others cautioned that intuitions can lead us astray, as seen in the historical resistance to moral progress, such as the shift in attitudes toward gay marriage. This dual nature of intuitions—sometimes insightful, sometimes misleading—demonstrates the importance of analyzing and questioning them, especially when they conflict with reasoned conclusions.

Philosophical frameworks like Aristotle’s notion of telos and utilitarianism provided additional lenses for examining moral intuitions.

From a teleological perspective, an action is judged by how well it fulfills its inherent purpose. For example, reproduction aims to produce viable and flourishing offspring and actions that undermine this purpose, such as incest, might be deemed immoral.

Utilitarian perspectives, particularly the distinction between act and rule utilitarianism, added further nuance. While act utilitarianism evaluates individual actions based on their outcomes, rule utilitarianism considers the broader consequences of general adherence to a rule. In the case of incest, rule utilitarianism might reject it due to the potential harm to societal norms and familial dynamics, even if a specific instance appears harmless.

The discussion concluded by emphasizing the role of open dialogue and empathy in resolving moral disagreements. Political and moral conflicts often arise from differing priorities rather than fundamentally opposed values. For example, a voter prioritizing economic issues might disagree with another focused on environmental concerns, yet both can acknowledge the importance of the other's priorities. Engaging in face-to-face conversations, listening charitably, and refraining from dismissive attitudes were identified as essential tools for bridging divides.

Finally, a cautionary note was raised about the dangers of thoughtlessness in moral decision-making. Hannah Arendt’s concept of the “banality of evil” starkly reminds us that harm often arises not from malice but from failing to think critically about our actions and their implications. This underscores the importance of moral reasoning—not as a replacement for intuitions but as a means of refining and, when necessary, challenging them.

Community Survey

For those who’ve attended our Curiosity Cafés, please consider taking our brief community survey. We are conducting this survey to gather feedback on our events, and it should only take a few minutes to complete. Your responses are completely anonymous and will be invaluable in helping us improve our offerings. Thank you in advance!

Upcoming Events

Curiosity Café: Bi-weekly on Tuesdays, tickets below!

About: For those of you who haven’t had the opportunity to join our Curiosity Cafés and are wondering what they’re all about: Every two weeks, we invite members of our community (that includes you, dear reader!) to come out to the Madison Avenue Pub to engage in a collaborative exploration of our chosen topic. Through these events, we aim to build our community of people who like to think deeply about life’s big questions, and provide each other with some philosophical tools to dig deeper into whatever it is we are most curious about. After our scheduled programming, we encourage attendees to stay and mingle over food and drinks.

We will be hosting our next Curiosity Café on Tuesday, February 4th, from 6:00 - 8:30 pm at the Madison Avenue Pub (14 Madison Ave, Toronto, ON M5R 2S1). Come and hang out with us, grab food, and read through our handout from 6:00 - 6:30 pm. Our structured discussion will run from 6:30 - 8:30 pm with a 10-minute break in the middle!

Please purchase a ticket using the button below the event description. If tickets are sold out, please contact us via Instagram (@beingnbecomingorg) or email (sophia@beingnbecoming.org), and we will let you know if we can accommodate you.

The topic of our next café is Vulnerability

It is often assumed that to be vulnerable is to be susceptible to physical or emotional harm. Consequently, portrayals and descriptions of vulnerability both in our day-to-day lives and in the media we consume are reductively negative, equating it with weakness, dependency, powerlessness, and passivity, among other things. At our next Curiosity Café, led by returning guest co-moderator Eirini Martsoukaki and our very own Sofia Panasiuk, we will discuss these common presumptions about vulnerability.

The first half of our discussion will be devoted to exploring manifestations of vulnerability in our daily lives: we will explore the language we use to talk about vulnerability (‘TMI’, ‘trauma dumping’, ‘building walls’) and the ways in which leaning into vulnerability can be difficult, unsettling, empowering, or transformative. In the second half, we’ll examine the social norms about vulnerability and what effects, if any, these norms have. In what contexts are we expected to be vulnerable? What are the consequences of having social norms or expectations around vulnerability? Has social media (e.g., Instagram, Reddit, X) enabled vulnerability to be shared and experienced in meaningfully different ways than before?

If you have accessibility-related concerns, please visit our Eventbrite Page. The event description includes some accessibility-related information about the venue and the event.

*a note about ticketing:

Recently, we implemented a change to our Curiosity Café ticketing system! All of our tickets are now Pay-What-You-Can, with an important exception**. It is important to us to be transparent with all of you, so here’s our reasoning:

We want to promote $ accessibility by only asking our attendees to pay what they can, while also allowing us to grow our capacity as an organization. We have some exciting new initiatives planned for 2025, so think of your ticket as an investment in our community and future work ❤️

We want to encourage ticket holders to attend so that as many people as possible can attend.

This requires less back-end monitoring to adjust ticket category quantities on Eventbrite.

As before, our suggested donation amount is $10. However, this is a very generic recommendation based only on os needs. We encourage you to adjust your payment according to this amount and your own financial circumstances.

**We will still have five free tickets available for our attendees. If paying anything at all is not financially feasible for you or our ticketing system presents some other barrier, please contact our Director of Community Programs, Sophia, at sophia@beingnbecoming.org. These tickets will be given away on a first-come, first-served basis, no questions asked! You can expect to hear back from her within 72 hours.

Arts & Culture: The Haywain Triptych by Hieronymus Bosch

The Haywain Triptych by Hieronymus Bosch is a masterpiece of Early Netherlandish painting that offers a complex allegorical representation of human sin and its consequences. Created between 1510 and 1516, this large oil painting on oak panels is currently housed in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, Spain.

The central panel features a large wagon loaded with hay, symbolizing worldly possessions and material wealth. This imagery is based on a Flemish proverb: “The world is a haystack; everyone takes from it what he can grab.” Hay represents the transient nature of earthly goods and the futility of avarice.

Christ appears in the clouds above the central panel, overlooking the scene with outstretched arms showing his stigmata. This represents divine judgment and the opportunity for salvation.

The triptych can be interpreted as Every Man’s journey through life, from the Fall of Man to the final judgment. It presents a stark choice between earthly pleasures, which lead to damnation, and spiritual contemplation, which leads to salvation.

While traditionally viewed as a pessimistic work predicting damnation for all of humanity, some scholars argue that The Haywain Triptych offers a glimmer of hope. The love scene atop the hay mound, where a woman closes her eyes to worldly temptations, may represent self-reflection and the possibility of choosing virtue over sin.

The triptych serves as a moral parable, exposing human avarice and encouraging viewers to contemplate their actions and seek redemption. It reflects the late medieval mindset, preoccupied with sin, judgment, and the transience of worldly pleasures.

Toronto Events

Chris’s Toronto Event Calendar

If you want more opportunities to connect, inquire and mingle with like-minded people, check out Chris’s calendar on Notion. Chris curates this calendar with events happening in Toronto. Events include thought-provoking lectures, group discussions, and workshops.

makeworld’s Calendar of Toronto Events

makeworld’s curated list of recurrent events in Toronto, which include tech meetups, lectures, unconventional comedy shows, and discussion-based events (like ours!).

Readings & Resources

Marybel’s Recommendation:

“Hume on the Emotions” by Amy Schmitter

The article gives an overview of David Hume's philosophy of emotions as presented in his "Treatise of Human Nature" (1739-40). Hume categorizes emotions (or "passions") as impressions of reflection, distinguishing them from ideas and impressions of sensation. He divides passions into direct and indirect, with direct passions arising immediately from pleasure or pain, and indirect passions requiring additional mental processes such as cognition and reasoning. To forward his position, Hume introduces the concept of a "double relation" to explain indirect passions like pride and love, which involve associative connections between ideas and impressions, linking causes, qualities, and objects of passions. Further, Hume describes sympathy as a mechanism for communicating passions between people, while comparison is a process that can produce contrasting passions. These concepts are crucial to Hume's understanding of social emotions and moral sentiments. This is where Hume famously argues that "reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions," emphasizing the motivational primacy of emotions over reason in human behaviour and moral judgments. Altogether, Hume develops a sentimentalist theory of morality, arguing that moral judgments are based on feelings rather than reason.

Sophia’s Recommendation:

“Two Psychologists Four Beers” podcast, hosted by Yoel Inbar, Michael Inzlicht, and Alexa Tullett

According to its About section, the podcast features two psychologists who endeavour to drink four beers while discussing news and controversies in science, academia, and beyond. I haven’t listened to it yet, but after discussing moral intuitions with Yoel last Tuesday, I am really excited to check it out!

Zach’s recommendations:

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s early 2000s work has shaped research on moral judgment and intuitions for over 20 years. In what became known as Moral Foundations Theory, Haidt posits that moral judgments are guided by intuitions relating to five types of values: harm, fairness, loyalty, respect, and purity. He notes the phenomenon of “moral dumbfounding”, whereby people sometimes struggle to rationally justify some intuitive moral judgments. He subsequently went on to produce research investigating the moral differences between liberals and conservatives, identifying differences in how each aforementioned value is prioritized. He synthesizes in his book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided By Politics and Religion. When I was an undergraduate student, Haidt’s work really sparked my interest in the study of morality. If you like videos, check out Haidt’s TED talk on The Moral Roots of Liberals and Conservatives

A notable critic of Moral Foundations Theory, Psychologist Kurt Gray offers criticisms in support of the Theory of Dyadic Morality. In his newly released book Outraged: Why We Fight About Morality and Politics and How to Find Common Ground, Gray synthesizes a variety of research that supports the primacy of the perception of harm when it comes to guiding our intuitions and subsequent judgments, arguing that Haidt’s moral foundations ultimately boil down to the different ways in which people perceive of and conceptualize harm. Furthermore, he outlines how differences in perceptions of harm (e.g., perceptions of who is vulnerable, threatening, and suffering) between people produce moral conflict and disagreements, especially in politics. Of note, he provides insight into how we can best reach others when engaging in moral disagreement. I’ve recently finished the book, and I must say, it is easily one of the best books that I’ve read in the past few years. For those interested in TED talks, Gray has a great video on Why We Fight About Morality and Politics. For those interested in some lighter reading without committing to an entire book, you can check out his article published alongside Samuel Pratt in the Annual Review of Psychology called Morality in Our Minds and Across Cultures and Politics.

Featured Quote

“Reason is, and ought only, to be, the slave of the passions”

- David Hume

Our mission is to present a diversity of perspectives and views. The views and opinions expressed in this newsletter are solely those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of Being and Becoming. Being and Becoming disclaims any responsibility for the content and opinions presented in the newsletter, as they are the exclusive responsibility of the respective authors. If you disagree with any of those presented herein, and you feel so inclined, we recommend reaching out to the original author and asking them how they came to hold that opinion. It’s a great conversation starter.