What is Knowledge?

Plus our upcoming café on the ethics of sexual desire, a contribution from co-moderator Eirini Martsoukaki, and more.

Introduction

By Adrian Ma

The pursuit of knowledge appears to drive a wide variety of human activities, from science to history to therapy to mathematics to forays into the darkest corners of Wikipedia. Often, our search for knowledge has its origins in curiosity, which is arguably the starting point of philosophy itself (as the Greek philosopher Plato wrote in the Theaetetus, “philosophy begins in wonder”). At our Curiosity Café last Tuesday, moderated by Eirini Martsoukaki and Marybel Menzies, we explored these—if not quite twin, then perhaps blood-related—concepts of curiosity and knowledge and questions surrounding the mysteries of each. In the recap below, I attempt to reconstruct with my very fallible memory some of the many ideas we exchanged and picked apart. But first:

Featured Content:

Curiosity Café Recap: What is Knowledge?

Community Survey

Upcoming Events

“Why Ignorance Loves ‘Curiosity’” by Eirini Martsoukaki

Toronto Events

Curiosity Café Recap: What is Knowledge?

By Adrian Ma

We are fans of curiosity here at Being and Becoming, as the name of this event series suggests. Tuesday’s café, however, began with an acknowledgment of curiosity’s double edge—both its potential to expand our horizons and its complicity in the death of a certain cat. As our co-moderators, Eirini and Marybel, write:

We all know the phrase, “curiosity killed the cat.” But what exactly does that mean when we gain so much from being curious in our daily lives? It seems curiosity can drive us to explore new places, ideas, and possibilities; however, it can also lead us astray. For instance, it is easy to see how the curiosity that is seemingly rewarded with new knowledge while endlessly scrolling through social media is often to one’s detriment. That is, the knowledge acquired tends to be time-consuming and not very fruitful, such as the knowledge that there’s a baby monkey somewhere that can do a backflip. On the other hand, curiosity can be immensely beneficial. For example, scientific progress is almost entirely driven by curiosity and the desire to know more about the world we live in.

From here, we explored the vices and virtues of curiosity, how we can cope with the discomfort of not knowing, how curiosity can be harnessed or cultivated, and what curiosity even is in the first place. Here’s what some of you had to say:

Curiosity, ideally, lies somewhere between indifference and obsessiveness. It should be strong enough to encourage investigation, but not to compel attachment to the object of interest.

For curiosity to qualify as such, it should be free of immediate need. My learning more about my cancer diagnosis to determine the course of treatment I ought to pursue can hardly be said to be motivated by curiosity.

Certain types of curiosity are explicitly goal-oriented—like the curiosity of scientists who conduct research to develop a vaccine—whereas other forms are more spontaneous and free-flowing.

Perhaps curiosity that is rigidly structured or goal-oriented doesn’t count as curiosity at all, because the latter should be flexible and open-ended, receptive to spontaneous appearances and encounters. In contrast, a tightly structured or narrowly focused attitude involves a sort of tunnel vision that is antithetical to curiosity.

Curiosity is always goal-oriented, either implicitly or explicitly. Even the seemingly unstructured and organic exploration of art, for example, can be said to be motivated by a desire for pleasure.

Curiosity is not always defined by an attraction to things we like; we can be curious about things we hate or know to be unpleasant, as in the phenomenon known as “morbid curiosity.”

The information overload enabled by modern technology—cellphones, the internet, social media—can suppress rather than foster curiosity. Sometimes, tuning out and disconnecting is more conducive to curiosity than subjecting yourself to a constant deluge of information. Curiosity needs room to breathe.

When we are curious about a topic, we tend to indulge it by exploring what other people who have studied or thought deeply about the topic have said. But sometimes, it is better from the standpoint of curiosity not to consult external sources of knowledge, but to sit with your thoughts and follow them where they lead. Going straight to the book or peer-reviewed journal might lead you to prematurely dismiss your own ideas and intuitions and defer to the authority of experts, thus closing off potential avenues of insight.

Taking up art is a great way of nurturing curiosity, because it opens up new ways of perceiving and interacting with the world; for many people, the old, stale, habitual ways of seeing have sapped the world of its wonder.

Navigating life would be impossible if I were curious all the time—that is, always questioning the veracity of beliefs we ordinarily take for granted. There might be a non-zero chance that the sun will fail to rise tomorrow, but constantly entertaining this possibility would drive anyone crazy.

After the break, our focus shifted from curiosity to its—for many—intended outcome: knowledge. Our moderators kicked things off by highlighting some of the age-old problems that have haunted classic philosophical theories of knowledge:

Among philosophers, there is much disagreement about what knowledge is and how we acquire it. Some philosophers, such as Plato, argue that knowledge consists in having a justified, true, belief. For example, for me to know what time it is: 1) it, in fact, must be that time, 2) I must look at a watch, to be justified, and 3) I must form a belief about the time. However, imagine the following scenario: Mike is looking at a clock that has stopped working. The clock shows that it’s 3:00 PM. Mike believes that it is 3:00 PM because he trusts the time shown on the clock. He is justified in his belief because he has reason to believe that the clock would show the correct time if it were working. By sheer coincidence, the actual time is 3:00 PM. Although Mike’s belief that it is 3:00 PM is both justified and true, it is due to an accident. Mike doesn’t actually seem to know that it is 3:00 PM. Given this limitation, other philosophers argue that all knowledge is gained from our senses. For example, when we know the sky is blue, it is because we had a sensory experience viewing the sky and its colour. However, problems have been noted with this approach, since our senses can be deceived, such as in illusion.

What are we to make of these challenges to classic theories of knowledge? Should we conclude (as some philosophers have) that genuine knowledge is impossible, or are there other ways to make sense of knowing? Can we have knowledge without sensory experience? And given all the ways in which we can be misled (such as by AI deepfakes) how can we identify reliable sources of knowledge and minimize our susceptibility to falsehoods?

Here are a few of your responses:

Justification for knowledge is not an all-or-nothing affair, but can be stronger or weaker depending on the evidence. In many cases, justification consists of a combination of reasons, which individually (“I heard it from a friend”) may prove very little.

If the world is always in flux, it seems to follow that knowledge is impossible, because knowledge is static and reality dynamic. A belief that is true in one instant would be false the next.

Can we know something that isn’t true? It seems that knowledge, by definition, is reserved for true beliefs.

We often use the word “knowledge” in a subjective sense, to denote feelings of conviction or certainty—even when the object of our feelings has not been proven true.

Is belief a purely intellectual affair? Many people form beliefs based on their emotions, and our minds can assent to the truth of propositions that our emotions seem to reject. In other words, we can often feel something to be true or false, even if our reasoning concludes otherwise. Is such internal division a sign we don’t actually believe something? Or is the approval of the rational mind enough?

Much of our knowledge is based on authority and trust, because no one can be an expert in all the things that are relevant to their lives. I trust my doctor to make judgments about my health, journalists to report the news, meteorologists to monitor the weather. Does this reliance make us particularly liable to misinformation and disinformation?

To some degree, access to the internet and its endless repository of information has made us less dependent on any particular authority (even if not on authority as such). If I am skeptical of what my doctor tells me, I can usually find a second opinion elsewhere.

Certain forms of knowledge, in theory, do not depend on sensory experience. Instead, they can be obtained through pure reason and an understanding of the concepts involved. “All bachelors are unmarried” and “a square is not a circle” are statements I can know to be true without appealing to the state of the external world.

At the same time, it’s hard to imagine how, in practice, we can know anything without some recourse to sensory experience. Even if we could, on paper, work out that 1+1 = 2 from within the emptiness of a sensory deprivation tank, this isn’t how anyone actually learns arithmetic—we do so by reading textbooks, learning from teachers, doing exercises and scribbling on blackboards.

Sometimes, knowledge feels like recollection (cue Plato’s theory of knowledge). We have all experienced that satisfying “aha” moment, when, upon learning something, we feel as though we are remembering something we have known all along.

Some forms of knowledge are independently verifiable (I can verify the accuracy of a politician’s assertion by checking statistics and reading the news), whereas others are not. Whether I truly love someone, for example, seems to be something only I can know—it can’t be decided by third parties on the basis of external evidence.

Why should we care about the truth beyond its practical implications? Does it really matter whether something is true, as long as it allows us to live comfortably and conveniently?

Yes, because the truth matters for its own sake!

Our moderators concluded our all-too-brief discussion with a takeaway prompted by a famous quote from Socrates:

Socrates famously claimed that his wisdom was in recognizing his own ignorance. That is, he said the one thing he knows is that “I know nothing.” If it is true that our knowledge is limited, then how do we both harness our curiosity and foster a sense of humility when our pre-existing beliefs are challenged?

That’s it for this recap. If you would like to learn more about our cafés, including the one we have planned for next week, check out the “Upcoming Events” section below. Then, if you know what’s good for you, scroll down just a few notches further to read co-moderator Eirini’s reflection on “Why Ignorance Loves ‘Curiosity’.”

One last thing: If you have attended any of our cafés (even if it wasn’t this one), please consider filling out our community survey. Your responses will be anonymous and will go a long way toward helping us improve our events. Thanks for reading. I hope your curiosity keeps you coming back.

Community Survey

For those who’ve attended our Curiosity Cafés, please consider taking our brief community survey. We are conducting this survey to gather feedback on our events, and it should only take a few minutes to complete. Your responses are completely anonymous and will be invaluable in helping us improve our offerings. Thank you in advance!

Upcoming Events

Curiosity Café: Bi-weekly on Tuesdays, tickets below!

About: For those of you who haven’t had the opportunity to join our Curiosity Cafés and are wondering what they’re all about: Every two weeks, we invite members of our community (that includes you, dear reader!) to come out to the Madison Avenue Pub to engage in a collaborative exploration of our chosen topic. Through these events, we aim to build our community of people who like to think deeply about life’s big questions, and provide each other with some philosophical tools to dig deeper into whatever it is we are most curious about. After our scheduled programming, we encourage attendees to stay and mingle over food and drinks.

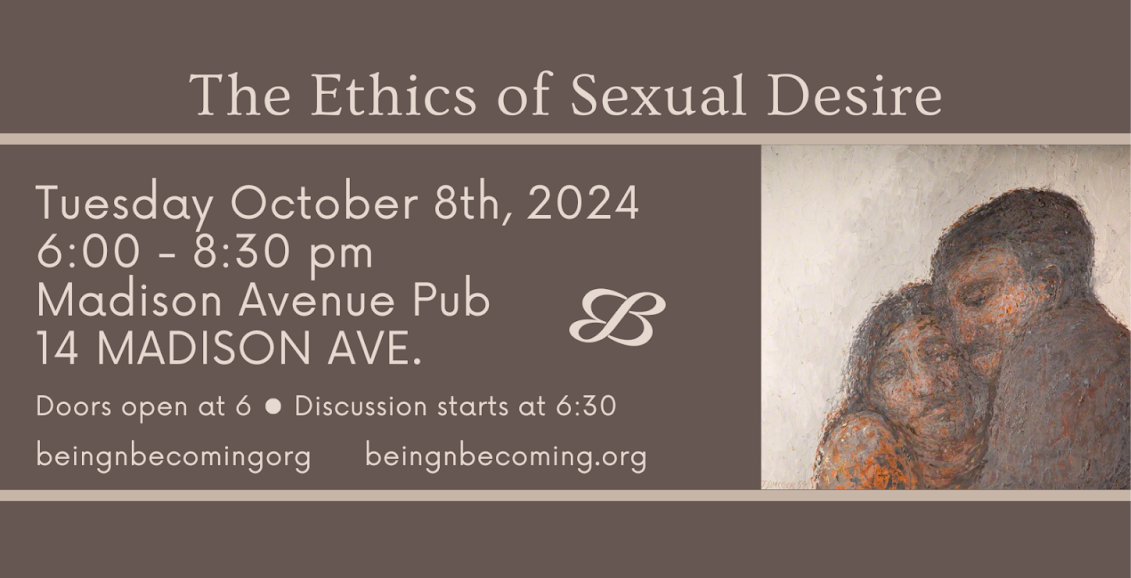

We will be hosting our next Curiosity Café on Tuesday, October 8th, from 6:00 - 8:30 pm at the Madison Avenue Pub (14 Madison Ave, Toronto, ON M5R 2S1). Come and hang out with us, grab food, and read through our handout from 6:00 - 6:30 pm. Our structured discussion will run from 6:30 - 8:30 pm with a 10-minute break in the middle!

Please get a ticket using the button below the event description. If tickets are sold out, please contact us, either on Instagram @beingnbecomingorg or over email at sophia@beingnbecoming.org, and we will let you know if we are able to accommodate you.

The topic of our next café is: The Ethics of Sexual Desire

Being gay isn’t a choice: as Lady Gaga puts it, we’re just “born this way.” In fact, none of our sexual desires seem like choices. We have a certain “type” we’re attracted to, we have things we like in bed, and it often seems like nothing can be said to explain these—we like what we like, and that’s all there is to it.

But surely our social world shapes our sexual desires: we internalize beauty standards from popular media; we learn how sex works through pornography; we often worry not just about what we desire, but what we’re supposed to desire.

How much might our sexual desires be shaped by our world? Is it possible that our sexual desires might be shaped for the worse? And if that’s true, what should we do about it?

The goal of this café is to provide a space where we can openly reflect on our own sexual desires and then philosophically discuss where they come from and why it matters. We’ll discuss questions such as:

What’s your type? What do you like in bed? Are you happy with these desires?

What influences our desires? And what should influence them?

Can we change our sexual desires?

Does it make sense to talk about sexual desires as being political? Do they ever reflect or reinforce inequalities or injustices in the world? Could reflecting on our sexual desires indicate what needs to change in our society and culture?

Join us at the next Curiosity Café on October 8th, with guest moderator Jules Sheldon and our very own Sophia Whicher, to discuss these questions and more!

Both the “Pay-What-You-Can” and “free” tickets serve as a ticket to our café! We ask that you consider making a donation by purchasing a “Pay-What-You-Can” ticket to help us make our work and growth as an organization possible. If you have accessibility-related concerns, please visit our Eventbrite Page—in the event description you will find some accessibility-related information about the venue and the event.

Why Ignorance Loves “Curiosity”

By Eirini Martsoukaki

One of the most troubling aspects of curiosity is its selective nature. Consider how often someone declares, “I’m just being curious!” as a shield against criticism. For example, a person skeptical about climate change might spend hours consuming videos and articles that reinforce their doubts, cherry-picking information that aligns with their beliefs.

This prompts an important question: is mere inquiry enough? It seems that curiosity involves valuing knowledge for its own sake, rather than using it to serve our own agendas.

But are good intentions enough to shield us from ignorance? The answer to this question is not as straightforward as it may seem, especially when we factor in social media. Algorithms curate our feeds based on our interactions, creating echo chambers where only similar ideas circulate. A politically liberal person will receive website suggestions that reinforce liberal beliefs, just as a politically conservative person will see content that supports conservative views. Ignorance thrives on this type of curiosity because it allows us to feel informed while we merely reinforce our biases. It’s all too easy to conclude, “I’ve done my research!” after consuming a few articles that confirm our existing views.

So, how do we guard against such ignorance?

Philosophers often argue that curiosity is best seen as a collective pursuit. They posit that curiosity truly flourishes not just through individual inquiry, but through engaging with others and actively seeking conversations with those who hold different beliefs. Philosophers often take this line of argument a step further, asserting that we have a duty to be curious in this way: by failing to actively seek out such conversations one commits some kind of epistemic negligence. This means that when we fail to seek out knowledge that challenges either our own perspectives or those of the status quo, we risk undermining both our personal growth as well as the collective well-being of society.

However, philosophers often fail to take into account that not everyone has the privilege to step into environments that encourage such exploration. For many, real barriers—social expectations, cultural norms, and mental health challenges, among others—can create a silence that feels insurmountable.

Recognizing this disparity reveals our responsibility: to create safe spaces where curiosity is celebrated. For those who have been silenced or marginalized, entering a space that values inquiry can be truly transformative. This is to say, if curiosity is best described as a collective pursuit, then prioritizing the creation of spaces for it to flourish is not just important—it is essential; without these spaces, a true collective cannot exist.

Toronto Events

Chris’s Toronto Event Calendar

If you want more opportunities to connect, inquire and mingle with like-minded people, check out Chris’s calendar on Notion. Chris curates this calendar with events happening in Toronto. Events include thought-provoking lectures, group discussions, and workshops.

makeworld’s Calendar of Toronto Events

makeworld’s curated list of recurrent events in Toronto, which include tech meetups, lectures, unconventional comedy shows, and discussion-based events (like ours!).

More than your regular Substack. Run by Misha Glouberman and friends, the Toronto Event Generator supports events through microgrants, finding venues, and promotion, and by creating listings of events they like.

Featured Quote

I can never read all the books I want; I can never be all the people I want and live all the lives I want. I can never train myself in all the skills I want. And why do I want? I want to live and feel all the shades, tones, and variations of mental and physical experience possible in my life. And I am horribly limited.

- Sylvia Plath

Our mission is to present a diversity of perspectives and views. The views and opinions expressed in this newsletter are solely those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of Being and Becoming. Being and Becoming disclaims any responsibility for the content and opinions presented in the newsletter, as they are the exclusive responsibility of the respective authors. If you disagree with any of those presented herein, and you feel so inclined, we recommend reaching out to the original author and asking them how they came to hold that opinion. It’s a great conversation starter.